The hottest year recorded on Earth was 2020. What does that mean for our future?

And the last decade was the warmest decade ever!

Hi! Welcome to Climate Matters, a weekly explainer newsletter on climate crisis written by me, Neelima Vallangi, a person who loves living on a beautiful and habitable planet. If that’s you as well, why not support Climate Matters and/or subscribe to the newsletter if you’re new here?

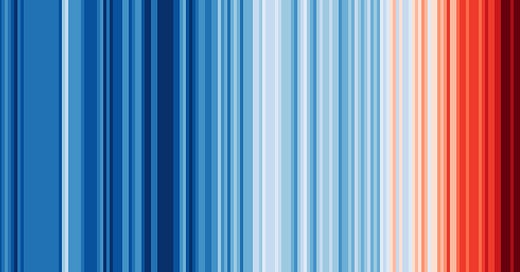

2020, the year that everyone is happy is no more has one last unwelcome, unpleasant record up its sleeve. 2020 is the hottest year ever recorded on earth. The temperature was about 1.25°C warmer than the 1850-1900 average.

Depending on which dataset you are looking at, 2020 either ties with 2016 as the hottest year so far or the second hottest year. But it is unanimously agreed that the difference between 2016 and 2020 is nominal and the last decade (2010-2020) is the hottest decade so far with relentless warming and heating up of the planet. The last six years of the last decade all were the top hottest six years the earth has experienced since pre-industrial times.

While NASA and Copernicus datasets find 2020 was the hottest year, Met Office and Berkeley Earth find 2020 was the second hottest year.

Before I talk about the implications and takeaways from this update, first a quick roundup of few relevant studies published recently that will help you make sense of the future implications of this record setting hot year.

A recent study found that current greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere, even without the extra future emissions, have already locked in warming that will blow past our Paris climate goals.

Another study last year found the earth’s atmosphere is much more sensitive to co2 concentration than we originally thought, meaning more warming is caused at a given level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere than we had previously accounted for.

Another recent paper found the oceans took an impossible 90% of the heat and ocean temperature (heat content) hit record high in 2020.

Another study found that it is highly likely that the earth’s atmosphere will cross 417ppm co2 concentration in 2021, which is 50% higher than before the industrial revolution, due to human-caused emissions.

What do we infer from all these and 2020 being the hottest year?

1. Heating is extremely uneven and this is extremely concerning.

The overall global temperature is about 1.2°C higher than pre-industrial levels today. But within this small increment, the Arctic was a record breaking 7 degrees warmer than usual in 2020. In the larger scheme of things, this anomaly won’t put any visible dent in the global temperature rise overall. But the Arctic did suffer massively as a consequence of this concentrated heatwave in a single year. This shows us the larger implication of small numbers like 1.5 or 2 degree global warming and how these seemingly small numbers mask a great amount of warming in different pockets at different times around the world. The global temperature rise is an average of the deviation of temperature at several data points collected all over the earth’s land and ocean surface, every day, over more than hundred years. This number is positively scary when you think of all the smoothened out averages during the last many decades and over many points across the world. Countries, cities and areas can have wildly high(mostly) or low(occasionally) temperatures deviating from the expected average for few days and that won’t show up significantly in the global temperature rise. Ergo, 1.5°C or 4°C aren’t small numbers and we need to take them with utmost seriousness because the average masks great variation across regions, seasons, time periods and impacts.

As per Berkeley Earth, 45 countries had record warm high temperatures compared to relative 1951 to 1980 averages in 2020. And it is remarkable that neither did any country have a colder than average year nor is the warming uniform. India warmed only by 0.4 degrees C but Russia warmed by 3.6 degrees C in the same year. While Siberia baked under record heat, India was flooded and battered by extreme rainfall and supercharged cyclones. And this seems to be a good representation of the future we can expect - either fire or flood all over. You can read the full Global Temperature Report for 2020 by Berkeley Earth here.

2. Crazy Hot Cities will be our future

Not only should the trend of uneven heating in specific places worry us, but also heat island effect is very real, observed already and it should worry us because inhabited land occupied is actually very very small compared to all land surface. As per Our World in Data, all our cities, towns, villages and built up human infrastructure cover only 1% of all habitable land surface. This means even if our cities bake in extreme heat, the effect will be masked when averages are taken and it will not be represented visibly in the overall global temperature rise. Like when the Siberian town had a day where temperature was 18 degrees above average in 2020, can you imagine what days with an excess of 18+ degree temperature in cities not built for heat like would be like? This concept is explained well in this article below.

Even when climate models simulate temperatures for urban areas, projections may be simplified in other ways. To produce monthly temperature averages, models might smooth out the peaks and troughs of individual days. Urban land may be fixed at its present extent and possible actions that cities might take to adapt to rising temperatures – such as more green spaces or reflective roofs – are ignored. Complex variations in temperature between streets are still not resolved either. This means that even state-of-the-art models probably underestimate the true severity of future warming in urban areas - Read more at what would 4°C of global warming feel like?

3. Oceans taking up 90% of the heat is, umm, bad news and also there’s some good news

To put global warming in very simple terms, all the extra greenhouse gases left in the atmosphere are trapping heat (that otherwise would’ve radiated back into the universe) and causing an energy imbalance in the earth’s system. We know from the law of conservation of energy that energy never disappears, it only changes form. All the energy that cannot escape earth because of the energy trapping greenhouse gas layer is in turn being absorbed by land or ocean. Turns out, a recent analysis, published in the journal Advances in Atmospheric Science, found just over 90 percent of the additional heat due to human-caused climate change has been absorbed by the ocean so far.

This means, only 10% of all global warming so far is absorbed by land and despite that the land warmed twice as high in 2020, setting a new record of reaching 1.5°C above average while the ocean was just 0.7°C above average, as reported by Berkeley Earth[*]. Just that minuscule 10% extra energy is causing very high levels of heating and heat-induced disasters such as droughts, wildfires and heatwaves on our terrestrial landscape. This should worry us because if we cross the threshold where the ocean can’t absorb as much heat as it does now, then any small increment in heat absorbed by land will lead to even more hot and miserable conditions on habitable land than what we’re currently seeing.

The analysis also found the temperatures in the upper 2,000 meters of the ocean hit a record high in 2020. Possibly not quite surprising then that 2020 had a record flooding and storm season worldwide. Because all that ocean warming translates to 1) increased moisture in the atmosphere which in turn means extreme rainfall in uneven quantities at unseasonal times, 2) a hyper active, supercharged storm season and 3) ridiculous indirect impacts such as locust plagues and crop destruction that directly threaten our food security among others. The hot ocean has been melting ice from stealthily from beneath as well apparently, as if we didn’t have enough to worry about.

However, the sliver of good news is that oceans can protect us greatly if we act in time, that is if we get to net zero emissions as soon as possible. Many scientists now believe there’s a good chance of halting warming in near future because oceans will play an outsized role in quickly absorbing the extra heat and stabilizing climate system far quickly than anticipated. Whether that is within 3-5 years of reaching zero emissions as one scientist predicts or a bit longer than that is slightly up for debate, but scientists do seem to agree that oceans will act as a giant buffer against the catastrophic impacts of warming as soon as emissions go down.

Until recently, Mann explained in The Guardian, scientists believed the climate system—a catch-all term for the interaction among the Earth’s atmosphere, oceans, and other parts of the biosphere—carried a long lag effect. So, even if humanity halted all CO2 emissions overnight, average global temperatures would continue to rise for 25 to 30 years, while also driving more intense heat waves, droughts, and other climate impacts. Research over the past ten years, however, has revised this vision of the climate system. Instead, if humans “stop emitting carbon right now … the oceans start to take up carbon more rapidly.” The actual lag effect between halting CO2 emissions and halting temperature rise, then, is not 25 to 30 years but, per Mann, “more like three to five years.”

- Read more on this in the interview with Michael Mann, one of the world’s most eminent climate scientists and the game-changing new climate science

3. The rate of warming is accelerating rapidly and dangerously.

When 2016 became the hottest year the earth had ever seen since temperature record keeping began, there was some chatter that the heating influence of a strong El Nino event caused the extreme heat in that year and that it was possibly an anomaly. By 2020, the carbon emissions rose so quickly that even without the warming effect of an El Nino event and despite the cooling effect of a La Nina event that kicked in towards the end of the year, the temperature rise was as high as 2016, in just five years. This confirms the rate of warming is accelerating rapidly. The last decade was the hottest decade the planet has ever experienced. And emissions are not reducing nearly as fast as we want them, so it’s not a surprise really that warming is accelerating then.

“The human-caused build-up of CO2 in the atmosphere is accelerating. It took over 200 years for levels to increase by 25%, but now just over 30 years later we are approaching a 50% increase, said Professor Richard Betts speaking to Met Office UK on their recent forecast that atmospheric carbon dioxide is set to pass iconic threshold in 2021. The 50% threshold is kind of important because scientists try to predict future warming by using something called equilibrium climate sensitivity(ECS), a concept which predicts what temperature can be expected at doubling(560ppm) of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

This magic number 560 comes from doubling the atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration of 280ppm observed during the stable, pre-industrial times. Essentially they try to estimate what happens when carbon dioxide in the atmosphere doubles from pre-industrial levels and how it will impact our climate system in the long term after the system stabilises.

Next year we’re likely to breach the midpoint between pre-industrial levels carbon dioxide and the future doubling event, as per this prediction. According to Met Office UK, the average CO2 concentration for 1750 -1800 was 278 ppm and a 50% increase on this (417 ppm) will be observed over several days in 2021. “Although "halfway to doubled CO2" not of any physical significance, it can nevertheless be considered a milestone that highlights how much humans have already altered the composition of the global atmosphere and increased the amount of a gas that warms the global climate,” as per the forecast.

Did you know you can share the the web version of this post with your network using the button below?

What’s the takeaway?

Adaptation and Mitigation needs to be the top priority for all governments immediately and at every level already.

If there’s one big takeaway from the dumpsterfire that was 2020, it is that both mitigation(emissions reduction) and adaptation(preparing for impacts) need to be ratcheted up by several more notches because we are doing neither and things are, to put it very mildly, getting very bad.

***

If you’re thinking now I sound like a broken record, read on.

Scientists have been warning about the same things like a broken record for at least 5 decades now. They’re even proving the same old things with more certainty just so the world would respond adequately at least now. What’s missing is the critical mass to get things going. If you didn’t learn anything new today in this newsletter, I’m glad you’re well apprised of the situation. Now please take the conversation forward and get more people involved/concerned. If you did learn something new today, I’m glad and please, now take the conversation forward to get more people involved/concerned.

Because, well, what’s been said below.

Share this article with your network, via social media or email.

For one of the next newsletter issues, I was thinking of putting together an explainer on climate jargon that annoys or confounds you. Please feel to hit reply or leave a comment and let me know what terms need a better explanation or public understanding according to you.

Climate Matters is 100% reader funded.

This independent newsletter is brought to you by paid subscribers. If you found this post useful, become a paid subscriber or make a one time contribution so I can keep writing these explainers.