Uttarakhand Disaster: What exactly happened and what do we learn from it a month later?

And what's the way forward for communities living in the shadow of increasingly unstable mountain landscapes?

Welcome to Climate Matters, a weekly-ish newsletter on climate crisis written by me, Neelima Vallangi, a person who loves living on a beautiful and habitable planet. If that’s you as well, why not subscribe (& make a contribution to my reporting fund) and ensure it keeps running?

Exactly four Sundays ago, on February 7, 2021, a massive chunk of ice and rock collapsed from a mountain side at 5600m in Uttarakhand Himalayas and triggered a devastating debris-laden flash flood that wiped out two hydropower projects, claimed over 200 unsuspecting lives and damaged two more hydropower projects downstream. As the news trickled on that Sunday, Himalayan and climate change scientists, observers and analysts started speculating on the possible trigger of the flash flood, a kind of rarity in winter months. And even as the story developed and journalists gathered more information on ground, there was an immediate resurgence of the long-standing tug of war between livid environmentalists and the complacent government on the rampant construction of hydropower and infrastructure projects in the ecologically fragile Himalayan state and whether these projects exacerbated the tragedy.

Four weeks later, most of the news cycle and social media seems to have moved from the tragedy but the search and rescue efforts are still underway with over 130 persons still missing. No one has been held accountable for the loss of life and property, no probes have been ordered and there has been no crime committed apparently! And yet, 200 people have died, over ₹1500 crores are estimated in infrastructure damages and so many productive man hours are lost in search, rescue and relief efforts. If it were upto the government, it is a natural disaster caused in part or in full by climate change where humans had no control. To few others, it is a man-made disaster that could’ve been entirely averted. So what’s the truth then? I think it is somewhere in between these two.

Let’s analyse.

Here are couple of questions and discussions that will help you gain a comprehensive understanding on many intersecting issues, limitations and ineptitude at play here.

First, what exactly happened? Was it a “glacier burst”? Or was it a landslide?

Before we go any further, I first need to get something out of the way, a pet peeve that has immensely grated on my nerves during the frenzied media coverage of the incident in India where they went ahead and invented a new term called “glacier burst” which means nothing really. There’s glacial lake outburst flood, commonly known as GLOF and then there is glacier collapse. A glacier does not burst, ever, until someone puts a bomb inside or something, but otherwise it just collapses or disintegrates. And a glacial lake can have a sudden release, when the volume of the water gets too much or there’s a crack in the dam holding the water together or when both happen at once. And so, there’s a glacial lake outburst flood.

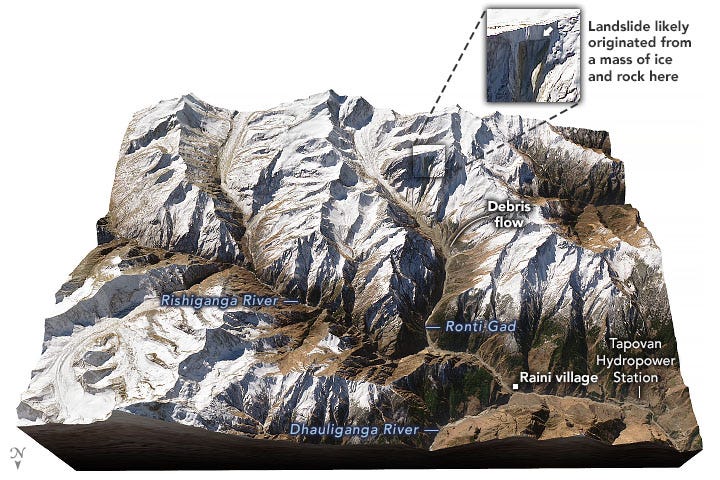

Now, coming back to the matter at hand, it is unclear to me at this point on whether there was a glacier involved or not (some experts think a hanging glacier collapsed). What we do know with some certainty is that it is a mountain slope failure that triggered a large landslide on a very steep gradient where a huge mass of rock and ice came crashing down into the valley with great force and gaining huge momentum in the process. The initial mass fell from a height of 5600m to 3800m straight into the valley below, where the Ronti gad (rivulet) flows. The Ronti gad then joins Rishi Ganga river, that further joins Dhauli Ganga river. The landslide debris and accumulated flood waters took the same path, from Ronti gad to Rishi Ganga river to Dhauli Ganga river, decimating and collecting whatever was in its flow path, from 40m high bridges to entire power projects.

While scientists are heavily leaning towards the landslide theory due to multiple lines of evidence, one thing that has flummoxed many is the lack of a clear explanation on where the disproportionate deluge of water came from, given there is no observable glacial lake in the region. Speaking to Scientific American, Dan Shugar, a geomorphologist at the University of Calgary, said that the friction of an avalanche creates a lot of heat, which could have melted much of the ice tumbling down the mountainside. “It's entirely plausible that all of that ice melted, just about instantaneously.” The cascade may have also impacted ice and frozen sediments in the valley and melted those, too.

Here’s a good visual explainer of the event from the terrific Reuters Graphics team - Disaster in the Himalayas: How a landslide sent a deluge of water, rocks and debris surging down

Additionally, if you’re interested in how these scientists and experts figured out what happened in Uttarakhand mountains through satellite data, here are some two great reads - Satellite images reveal 550m ‘scar’ left by Uttarakhand landslide in Nanda Ghunti glacier & Miniature Satellites Reveal Cause of Deadly Uttarakhand Flood That Devastated Dams

The cause of the deadly flood is more or less clear at this point and field research + analysis is ongoing and several scientists are trying to figure out where the incredible volume of water came from, so we’ll probably soon get an answer to it. Meanwhile, let’s move onto the next discussion point.

Was the 2021 disaster similar to the 2013 cloudburst disaster in Uttarakhand?

No.

The 2013 incident was ascertained to be a lake outburst flood triggered by extreme rainfall. Looking back at the visuals of the incident now, I’m shocked at our complete lack of disaster preparedness and monitoring. Kedarnath town was situated a mere 1.5km away from a lake called Chorabari (or Gandhi Sarovar) at a height of 3,845 m which is a such a risky situation, especially in times of climate change-fuelled extreme rainfall and rapid glacial melting. As per this report, between June 15 and 16, 2013, the region received over 300mm of rainfall filling the lake that had been left behind by the retreating Chorabari glacier. This is not a proglacial lake though, apparently. The lake is fed by snow and rainfall but not the meltwater from the glacier. The night’s deluge in terms of extreme rainfall led to the breaching of the moraine dam wall, emptying the huge volume of water into the valley below, sweeping away an entire town and causing as many as 5700 deaths and billions in private and public property and infrastructure damages.

What surprised me most about that incident, as covered in this Hindu report(The Lake Overflowed), was that there was an advanced weather station and a monitoring team present on site, watching the incessant rainfall filling up the lake, but weren’t able to warn anyone downstream. They couldn’t even warn Kedarnath town that was right within their sight, because phones were not working! What is this? 1838?!

But to summarise, the 2021 incident was due to a landslide/slope failure and the 2013 incident was due to a lake outburst flood triggered by heavy rainfall. Which brings us to the most important question…

Were these climate change/natural disasters or a man-made disaster?

Now, before we get into this, let us do a quick review of the terms hazard and disaster. Hazard is something that can be dangerous, it can be as simple as a busy traffic junction to a glacier high up in the mountain. Risk is the probability of the hazard actually materialising and causing harm to humans like a terrible accident or glacier breaking off. Disaster is when a hazard happens and causes widespread devastation to humans. For instance, let’s say two glaciers collapsed in two adjacent valleys at the same time. One valley was uninhabited and no one died and there was no infrastructure loss, that event will not be termed a disaster. The other valley where people were affected, will be termed a disaster.

First, what’s a natural and what’s a man-made disaster?

So when we think of the both the 2013’s lake outburst flood and 2021’s landslide triggered flash flood, both these events became such huge disasters simply because humans were in the direct path of destruction and did not prepare for it. Now, there are once-in-a-century extreme events like a big earthquake, a severe cyclone, an unprecedented flood or drought which occur as part of earth’s natural process, for which we possibly cannot fully prepare and we will have to bear the devastating consequences. These are natural disasters, out of our control and they can be termed as “act of god” in insurance terminology, simply because 1. no one is single handedly responsible for the occurrence of the event, 2. it is impossible to predict such events ahead of time with accuracy and 3. the scale of the disaster is so huge that it cannot possibly be managed or prevented in its entirety.

However, when we know that these potentially destructive flash flood hazards are materialising with increasing frequency and intensity, and we still are not responding adequately in terms of monitoring, disaster preparedness and risk mitigation, can we really call it a natural disaster or were these simply a failure to prepare and respond accordingly?

Now, what role did climate change play in causing the events that triggered the disaster?

This attribution is a bit tricky and will need scientists to invest a lot of time in analysing the past and current data, geographical and environmental features, modelling outcomes etc etc to give a clear answer. I’m not aware of any climate change attribution studies done on either of these two events at the moment. However, in general we know two things for sure. That the temperature is rising rapidly and causing ice to melt faster than it normally would and that extreme rainfall is also increasing as a response to warming temperatures.

In the 2013 event, Uttarakhand received a ridiculously high amount of rainfall in a very short time that filled up the lake that eventually burst its banks and flooded the entire downstream river basin. In the 2021 event, the winter temperature was abnormally high in Uttarakhand, in fact January 2021 was the warmest January on record in Uttarakhand for six decades. If this were an ice collapse incident, could’ve been easier to attribute warming to the event. However, this was a rock slope failure, as in a piece of the whole mountain collapsed. Scientists believe the freeze and thaw of the ice trapped between the rock fractures may have caused the failure of the rock slope.

The important thing to note here is that both landslides and extreme rainfall are normal occurrences. However, when their timing is odd or when the frequency of such events has increased abnormally, that can be partly or fully attributed to climate change. With the information we have on warming temperatures, increased extreme weather events and other lines of evidence such as similar incidents across the world where climate change has been proven to have contributed to the occurrence of the event, we can reasonably speculate that climate change has influenced both these happenings in some way.

To read more on this, two excellent explainers by credible scientific organisations below.

Understanding the Chamoli flood: Cause, process, impacts, and context of rapid infrastructure development by International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD)

Factcheck: Did climate change contribute to India’s catastrophic ‘glacial flood’? by Carbon Brief

// New Update:

The [ICIMOD*] analysis is significant because the Defence Geo-informatics Research Establishment, under Defence Research and Development Organisation, had recently said the tragedy was not “immediately” a human-induced disaster. “There is a need to look upon the demographic pressures in a systematic way but as far as this particular tragedy is concerned in our preliminary investigations the role of human activity is not the immediate cause... It [glacial breach] was far away from the area where several constructions [NTPC hydel power project in Tapovan and Rishi Ganga hydel plant] are taking place,” said Lokesh Sinha, director of DGRE, as reported by Hindustan Times this morning.

This is very important in the context of attributing responsibility and culpability because if the government declares it a natural disaster and not a human-induced disaster, then no one has to be held responsible and nothing much has to change in terms of development mechanism or priorities. But the overwhelming evidence is that human activity definitely exacerbated the impact of the disaster. //

Did Hydropower or Development Projects exacerbate the tragedy?

This was exactly the question Supreme Court asked in the aftermath of the 2013 tragedy and constituted an expert body(EB) to investigate and submit a report and recommendations. The EB did their study and came up with a 250+ page report, which can be accessed in full here and a readable summary can be found here.

The key findings were that Hydropower projects did increase the impact of the disaster, and they also caused destabilisation and degradation of the fragile environment in various ways and hydroelectric projects should be given approval only after thorough Environmental Impact Assessments and Social Impact Assessments. The EB also recommended scrapping of 23 out of 24 approved hydropower projects in Uttarakhand at that time.

And what did the government do after the report was submitted?

The Supreme Court agreed and banned new hydropower projects following the findings of the report by the expert committee in 2014. The government, then challenged the SC ban and also came out with their reports saying “hydro projects had no role in the Uttarakhand flash floods”, as per this article. Unfortunately, this case and several other cases related to hydropower projects have been in various states of limbo ever since, much to the detriment of the people in Uttarakhand.

Here’s a comprehensive update on the court cases - What Have Courts Been Doing about Dams? on The Quint

But do hydropower dams make sense in the Himalayas?

After the latest incident, the same argument has once again resurfaced on whether hydropower projects exacerbate these tragedies? And whether the financial, environmental and social cost exacted by these projects justify its continued existence in the current form in environmentally fragile regions like Himalayas. The answer to this question is not straight forward. Here’s why -

First, hydropower is considered a renewable energy and it is one of the most abundantly available energy sources that can be used in the mountains to generate electricity. Energy access is a prerequisite for development and the millions of people scattered all across the remote mountain areas do benefit from electrification. In some ways, a hydropower project is definitely preferred to a thermal power plant that will cause more warming and more destabilisation of glacial landscapes by extension.

On the other hand, the environmental degradation caused by hydropower plants is increasingly impacting the local ecology and the projects themselves are at high risk from glacial hazards and flash floods like we repeatedly saw in Uttarakhand. Even in the most recent case, if the hydropower projects weren’t there in the path of the flood, 200+ lives of the workers in the two wiped out projects would not have been lost to begin with.

So what’s the solution here?

While it is imperative that road access, infrastructure development and electrification must come to millions of people living in the shadow of Himalayas, old paradigms of development and impact assessments that do not take into the account the massively altered reality of a warming world will only create more havoc than benefits that can be reaped.

Immediately after the incident, Uttarakhand Chief Minister tweeted this -

As you can see here, hydropower and infrastructure projects are by default considered green and important despite the massive environmental, economic and social costs. By now, we know this is simply not true. Acknowledging this is the first step in actually mitigating the risk to development from climate hazards. Second, given the elected leaders stay in office in terms, short term thinking always trumps long term planning and this cannot be the way forward when the actions we take today can have catastrophic implications just few years down the lane, by which time leaders in office have been replaced and no one in power can be held accountable. Third, it is absolutely necessary to incorporate the latest science into planning of infrastructure projects, this means thorough research and analysis on glacial hazards and mountain landscapes to begin with. And it is equally important to have a monitoring and early warning systems, disaster preparedness and risk reduction strategies in place if one is going to build infrastructure in risky environments like the fragile Himalayan region.

What can actually be done to have sustainable hydropower development though?

I am not the expert on this so I will point you to expert sources. Take some time and go through these resources if you want to understand the complexity of the interconnected issues of development, energy production, environmental protection and climate change.

1. Hydropower : Need More Or Not In South Asia? An excellent panel discussion among leading experts on climate change, hydropower and engineering

2. “With rising energy demand in Asia, the high potential for hydropower development and the need for low-carbon energy development, hydropower would seem to have a significant role in South Asia’s energy future. However, the extent of hydropower development will depend on several risk factors, including the cost of alternative energy sources, the environmental sustainability of hydropower and social issues of equitable development.” — as per a recent paper published in International Journal of Water Resources Development: The role of hydropower in South Asia’s energy future

3. On Uttarakhand floods, solutions of yesterday no match for challenges of tomorrow. Read more at https://carboncopy.info/uttarakhand-floods-solutions-of-yesterday-no-match-for-challenges-of-tomorrow/

****

If you’ve read this far, congratulations. I applaud your commitment in getting to the root of the issue and not falling for easy, shallow explanations. :)

Leave a comment and let me know what you thought about this post, have any questions/comments/corrections or if you want start a new discussion on the topic.

Additional reading:

The Himalayan hazards nobody is monitoring - https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-56247945

The Science and the Political Economy of the Rishi Ganga Flood - https://science.thewire.in/environment/the-science-and-the-political-economy-of-the-rishi-ganga-flood/

85% Districts in Uttarakhand Vulnerable to Extreme Floods - https://www.ceew.in/press-releases/85-districts-uttarakhand-vulnerable-extreme-floods-ceew

A Month Since Chamoli Disaster, Scientists Have Reason To Anticipate More - https://science.thewire.in/environment/uttarakhand-chamoli-disaster-not-a-standalone-incident-more-to-come/

Climate Matters is 100% reader funded.

This independent newsletter is brought to you thanks to the support of 100+ paid subscribers. Support in whatever way you can and do share the newsletter so I can keep writing these explainers!

www.wdcpower.com has the answer to power production problem which solves no resource consuming after setup non polluting low cost low maintenance. BUT political and industrialist threaten to stop its deployment. We must band together and help John Rosebush get this to the UN as protections are needed to safeguard for the people.

This is amazing. I too had this in mind as to why is the government not responsible for their own actions ? So much of the tax money is being wasted in the name of development. So many lives are being swept away for electricity that is not even available to the state !